TONY ABBOTT: And we were also quite up-front, Fran, that we would get the budget back under control. You might remember the mantra, it was “stop the boats, repeal the carbon tax, build the roads of the 21st century and get the budget back under control”. So people, I think, were on notice that we were going to do what was necessary to ensure that we were not being a burden on our children and grandchildren. FRAN KELLY: I wonder how you think, though, that people were "on notice" that they weren't going to receive cuts to their pensions or weren't going to see cuts to health or cuts to education when you said there would be no cuts to health, no cuts to education. You said it over and over again. Why did you think you could get away with saying that if you weren't going to deliver that? TONY ABBOTT: But Fran, again, we have a very serious problem here - a problem where we were living beyond our means. And the first duty of government is not to do what's easy but to do what's right and necessary for our country. And we could not go on running up massive debts for our children and grandchildren to pay. That would be a form of inter-generational theft. FRAN KELLY: I think you've got a problem, though, in terms of trust. I mean you are saying now, I think what you're saying, is that the promise to restore the budget was always paramount, but I don't think everybody who heard the other promises thought that. And so now how do we know in the future what to believe when you say things and what not to believe? TONY ABBOTT: Well I know that people hear different things. Someone can say... FRAN KELLY: Well you said them. TONY ABBOTT: …and people hear different things. We constantly talked about Labor spending like a drunken sailor. It was always obvious that we were going to have to rein back unsustainable spending. We constantly talked about Labor indulging in a cash splash with borrowed money. And now we've done what is necessary. Look, we could have continued to try to fool people and say "you don't have to change" but that would, frankly, have been pretending to people that our country could somehow go on living on borrowed money.Here, Mr Abbott claims that he never lied; that he never broke any of his promises, and yet, in the same breath, implies that it was necessary to break promises to meet his overriding commitment to fix the budget. I believe that's commonly referred to as a contradiction. Mr Abbott states that “it was always obvious we were going to have to rein back unsustainable spending”. If so, then why rule out so many cuts prior to the election?. It is easy to see why the government is suddenly taking a beating in the latest polls. Lies and broken promises are not popular. But neither are they of much substance. I would much rather see the debate shift from the truthfulness of the pre-election commitments to the substance of the post-election policy directions. So let's look at some of Mr Abbott's arguments in his interview on Insiders. Australia's "debt problem" Mr Abbott told us that "we have a very serious problem here - a problem where we were living beyond our means. And the first duty of government is not to do what's easy but to do what's right and necessary for our country. And we could not go on running up massive debts for our children and grandchildren to pay. That would be a form of inter-generational theft." What is Australia's government debt level like, and is it really a problem? As Michael Keating, former Secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet and former Secretary of the Department of Finance points out,

Australia has a triple AAA credit rating, whatever that is worth. More pertinently general government net financial liabilities in Australia in 2013 represented only 11.8 per cent of GDP, compared to an average of 69.1 per cent for the OECD as a whole, including 81.2 per cent in the US, 40.4 per cent in Canada, 65.4 per cent in the UK, and as high as 137.5 per cent of GDP in Japan, and all these countries have low interest rates and no particular difficulty in financing their debt. Furthermore, although low debt is properly seen as providing increased scope to intervene in the event of an economic downturn, each of these countries had much higher debt than Australia in 2008 and they were still able to intervene and further increase their debt in response to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).Maybe you're a visual person. Below is a chart similar to ones you've probably seen a million times by now, but there is no harm in seeing it again. It shows the extent of Australia's debt compared with other nations. Government net debt (% of GDP) in 2013

Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor 2014, April 2014 (*emerging economy). Since the 1970s, Australia's government net debt has averaged around 7% of GDP. Given we are emerging from a period of sluggish growth, reduced revenues, and increased spending during the initial period of the global recession, a level of debt around 11-12% is remarkably low and can easily be serviced by a government (almost) on track to return to budget surplus. Australia's "deficit problem" Mr Abbott claims that they "constantly talked about Labor spending like a drunken sailor. It was always obvious that we were going to have to rein back unsustainable spending." I'm not sure he's entirely thought through this statement. Are drunken sailors really so profligate? How can they spend much money if they spend so much of their time at sea? Presumably, Mr Abbott meant that Labor was wasteful with the Commonwealth treasures. Let's assume, hypothetically, that the current government believes that we really do have an emergent problem with deficit spending. If this was the case, we would expect to see a government reining in spending. But this is not the case. As I showed in my previous post, the deficit is set to worsen under this government, despite its many cuts. Stephen Koukoulas has done some simple maths showing that the new government will be a bigger government than the previous:

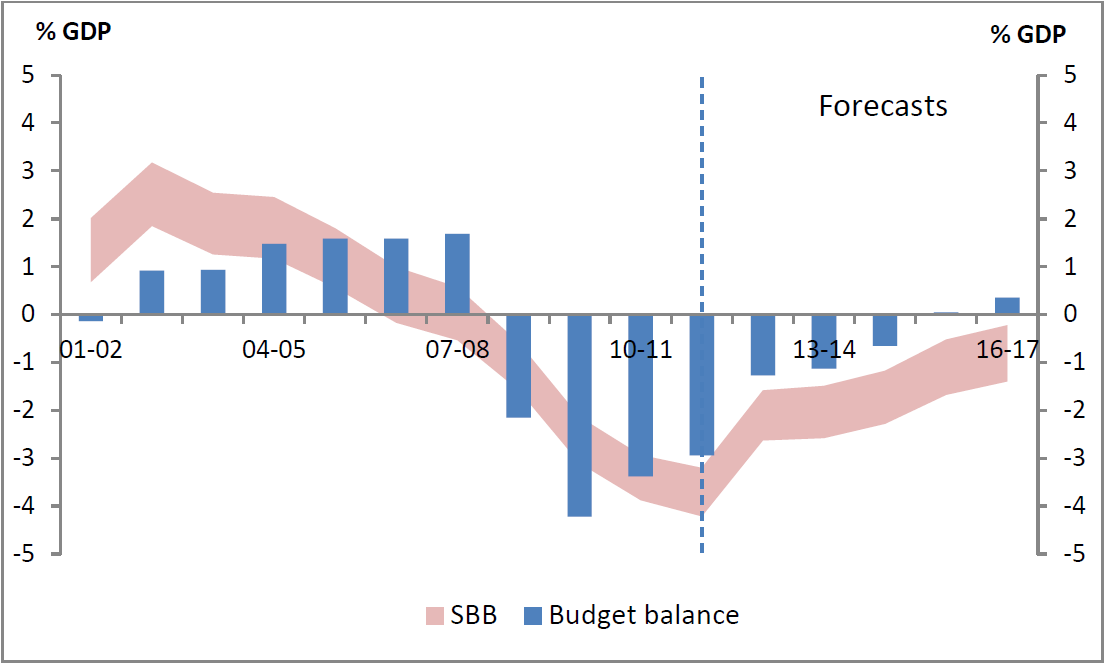

It is early days for the Abbott government, to be sure, but the budget shows that the size of his government will be 49.1 per cent of GDP, calculated on the period from 2014-15 to 2017-18. This is a smidge below the Howard government (49.2 per cent) and the Hawke/Keating government (49.6 per cent), but is significantly larger than the Rudd/Gillard government (47.4 per cent).Spending under this government for the period 2012-13 to 2016-17 will rise marginally from the 20.7% of GDP estimated in the Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook to 20.9% of GDP in the budget papers. The Coalition Government will also be relying on a larger tax to GDP ratio to fund its budget than the previous Labor Government. It seems the Liberals are the party of small government in rhetoric only. Talk of emergencies aside, the government does have a problem with deficit spending. Australia has a structural budget deficit. This essentially means that over the long-run, if all of the ups and downs of the economic cycle were flattened out, the government would still be spending more money than it raises. But this structural deficit is not the fault of the previous Labor Government. As a report by the Parliamentary Budget Office and another by the Australian Treasury show, the structural budget balance peaked in 2002-03 and has been declining since, due to generous tax cuts in the second half of the Howard Government and a shrinking tax base (particularly the GST) since the global financial crisis. Personal income tax cuts alone are considered to make about around two thirds of the decline in tax receipts. This may be difficult news to take for those who cling to the accepted wisdom that Howard delivered unending budget surpluses, while Labor squandered his savings. The truth is that the strucutral budget declined long before Labor took office, and our economic boomtime kept the dollars rolling in, although in smaller quantities than should have been the case. Once the global recession hit home, the established structural deficit made it all the more difficult for the Labor Government to achieve a real budget balance. The graph below, published by the Parliamentary Budget Office, shows how the structural budget balance (the pink line) dropped well before the actual budget balance (the blue bars).

Copied from Estimates of the structural budget balance of the Australian Government 2001-02 to 2016-17 But surely Labor's wasteful ways exacerbated the problem! Let's check the numbers. In the four years from 2009-10 to 2012-13 Labor kept real average spending growth to less than 2% per year, which was the lowest four-year period of real spending growth in 23 years. In Labor's final budget (2012-13), spending was cut 3.2% in real terms. Spending dropped from 25.2% of GDP in 2011-12 to 24.3% of GDP in 2012-13. The average level of government spending over the last 30 years was 25%, and the average during the Howard Government was 24.1%. Hard decisions The Coalition Government has talked a lot about hard decisions and heavy lifting. On Insiders, Mr Abbott proclaimed that "the first duty of government is not to do what's easy but to do what's right and necessary for our country". He also nobly declared:

This is all happening because we were living beyond our means. The former government gave us the six biggest deficits in our history. It was debt and deficit stretching as far as the eye can see. We are not doing this because we are somehow political sadomasochists. We are doing this because it is absolutely necessary for the long-term welfare of our country.Presumably, this means that promises must be broken to meet the overriding objective of fixing the budget. But, as shown above, the government is not fixing the budget. Spending is now even higher, and deficits even greater and more numerous. So what are the "hard decisions" (a euphemism for budget cuts) achieving? To answer that question, we need to go back to the previous term of government, when the Coalition was in opposition. There are two ways to approach opposition: relentless negativity or selective differentiation. To risk making the most obvious statement of all time, the Coalition Opposition of 2010-2013 adopted the former approach. Relentless negativity is powerfully effective in stirring up resentment against the government, but makes it difficult to map out alterntive options. Any new attempts by the government to raise more revenue are shot down as an attack on ordinary Australians or a blight on the economy. Any spending cuts are callous and unfair. The trouble that the Coalition faced with this approach was, that as the election loomed closer and closer, it became ever more difficult to change tac. After years of opposing everything, it is difficult to switch to selective differentation - agreeing on some policy issues, and setting out genuine alternatives to others. In the end, the opposition headed to the election promising to do more than they could ever deliver: scrap the carbon tax, scrap the mining tax, reduce company tax, increase defense spending, increase paid parental leave entitlements, don't cut education or health spending, don't touch the pension, don't touch Medicare. You couldn't even bake a magic pudding with an ingredient list like that. In order to cover the costs of some commitments, the government has had to break some of its others. The "hard decisions" we're hearing about aren't aimed at addressing the wasteful excesses of Labor; they are the result of the Coalition's relentless negativity and inability to set out a credible alternative in opposition. Abbott lied about what he could deliver in government, and, as he deals with consequences, he clearly continues to have a problem with the truth. And now for something completely different...

No comments:

Post a Comment